MARY LOU WHITNEY: SAVIOR OF SARATOGA

Marylou Whitney: The Savior Of Saratoga

She could’ve used her fortune and power for anything. She chose Saratoga and our racetrack.

Everyone who’s ever called Saratoga home is keenly aware of the great impact Marylou Whitney’s had on the city, but, in turn, that Saratoga wasn’t always the incomparable tourist destination it is today. While most Saratogians can robotically recite the following, decidedly dour historical footnotes, know that Marylou actually lived them. “Everything at the time was dead here; the track was dead!” Marylou has said of Saratoga when she first arrived here as a newlywed in 1958. “You could roll a basketball down the center of town and not hit anyone.” Her husband, Cornelius “Sonny” Vanderbilt Whitney, encouraged his new bride to help save Saratoga Race Course and the town itself, and thankfully, she agreed. “Sonny, with your money and my enthusiasm and work, we can light up this town!” said Marylou. And light it up she did.

Marylou Whitney had four children with her husband, Frank Hosford, and a fifth with Sonny Vanderbilt Whitney.

I first interviewed Marylou in 1987 for Adirondack Lifemagazine and covered her on and off throughout the years for Times Union, The Post-Star and The Saratogiannewspapers, and also within these pages. Sonny was 88 and Marylou 61 when I first visited them at Cady Hill, their 21-room, 135-acre estate on Geyser Road in Saratoga. A financier of the company that would become Pan American World Airways and founder of the theme park Marineland of Florida, Sonny was a decorated veteran of World War I and II, having served as Assistant Secretary of the Air Force and Undersecretary of Commerce. He’d also helped finance film classics such as Rebecca and Gone With The Wind. Marie Louise “Marylou” Schroeder was born on December 24, 1925, and grew up in Kansas City, MO. She attended the University of Iowa, but, at the tender age of 19, returned to Kansas City after the death of her father, taking a job at the local radio station where she hosted the popular broadcast, Private Smiles, for servicemen during World War II. (The show later earned her a Woman of the Year award from the USO, and one of Sonny’s horses was named Pvt. Smiles in her honor.) In 1948, Marylou wed her first husband, Frank Hosford, heir to the John Deere tractor fortune. The couple had four children—Marian Louise, Frank, Henry and Heather—but divorced, leaving Marylou to raise them by herself. “Marylou was beautiful,” says 88-year-old Fred Ryan, who was Superintendent of Service at The Gideon Putnam when he first met her in ’58. “I had just brought their luggage up to their suite, and I remember that she was wearing her blonde hair on top of her head,” he tells me. “I remember her being so friendly—she told me about her background and her children.” When Sonny was married to his third wife, Eleanor Searle, Ryan tells me that he worked as a bartender and waiter at Cady Hill. “The next season, when I showed up for a party, Marylou remembered me from her visit at the Gideon Putnam hotel,” says Ryan. “From that day on, every time I’d see her at the track, she’d nod and smile at me.”

During a stint in New York City pursuing an acting career, Marylou befriended actress Audrey Hepburn and author Truman Capote, a Yaddo fellow who’s said to have used her and three others as a composite for the star of his Breakfast At Tiffany’s novella, Holly Golightly (whom, ironically, Hepburn would later portray on the silver screen). With her acting career gaining steam, the then Marylou Hosford—at the time, separated from Frank—met Sonny at a supper club in Phoenix, and he hired her to star with Brandon de Wilde and Lee Marvin in his film The Missouri Traveler, which hit the big screen in 1958. Marylou then traveled to Sonny’s 100,000-acre Adirondack estate—land that his grandfather consolidated for $1.50 an acre—to act in another film, The Healing Woods. Sparks flew between Marylou and Sonny, and the couple fell in love. Needless to say, the film never saw the light of day. “Sonny said the reason he never made the picture is that he married me instead, and he didn’t want his wife to be a movie star!” Marylou has said of the time. Not skipping a beat, Sonny said, “I think I chose correctly.”

(from left) Walter M. Jeffords, Sr., owners Sonny and Marylou Whitney, jockey Bill Hartack and trainer J.J. Greely, Jr. at Saratoga Race Course in 1960, after the Whitneys’ horse, Tompion, won the Travers Stakes. (National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame)

Marylou and Sonny honeymooned in far-flung Flin Flon, Manitoba, headquarters of the Hudson Bay Mining & Smelting Company, which he’d founded. “We traveled three days and three nights by dogsled,” Sonny said. “It was 60 below.” They lived for a year with Marylou’s four children at Camp Deerland in Long Lake, NY, then moved to Lexington to settle on the Whitney family’s 1000-acre horse farm. (Sonny and Marylou had one child of their own, Cornelia, in 1959.) Sonny inherited his father’s racing stable, as well as his grandfather’s land, and named one of their broodmares Hush Dear, in Marylou’s honor. (It was one of his pet names for her, after she told him that saying “shut up” was too harsh.) As age 90 approached, Sonny told me: “I’m out of pictures, out of horses, out of mining.” He’d even considered selling Cady Hill, but Marylou had loved the old stagecoach house too much to give it up.

In 1992, five years after our first encounter, Sonny died at age 93, and he’s buried at Greenridge Cemetery in Saratoga, the town he considered his real home—of his nine residences at the time. Three years later, the widowed Marylou ventured to the South Pole on an expedition. Then 71, Marylou fell for 32-year-old John Hendrickson, a former tennis champion and aide to Alaska Governor Walter Hickel. (The two had clearly been seeing each other beforehand, as she confirmed during the ’96 Saratoga racetrack meet that she would be marrying him the following year.) John proposed to Marylou, in style, at Buckingham Palace—at a reception for Prince Philip, who joked that he wasn’t going to pay for their impending nuptials. (He didn’t.) Governor Hickel presided over their marriage in ’97, and the couple later named a horse in his honor. Irreverent and smart, John was the perfect complement to Marylou, and proved gentle and supportive after her stroke in 2006, following back surgery. John has always joked about their 39-year age difference. With his irreverence at full tilt, he raised more than a few eyebrows at the Saratoga Springs Rotary Club when he announced, “We’re expecting.” I was relieved to learn that they’d just bought a new puppy.

While I could fill an entire issue of saratoga living listing Marylou’s charities, honors and philanthropic work—she’s been especially generous to Saratoga Hospital over the years—it’s always at her annual Opening Day luncheon at the track when she and her beloved city seem to come alive, with Marylou presiding as its Grande Dame over a Who’s-Who of friends, politicians and local celebrities. Just like any international star, Marylou has a fan base—especially one in her adopted hometown. At her über-popular Whitney Gala, which came to an end in 2012, I watched throngs of well-wishers gather outside the Canfield Casino, saying hello to her as if only a few weeks had passed, saving the party favors she threw out into the crowd. Marylou fans will often paste tiny photos of her with plastic horses and fences to their hats for the track’s annual contest. She’s as close to Saratoga royalty as there’s ever been.

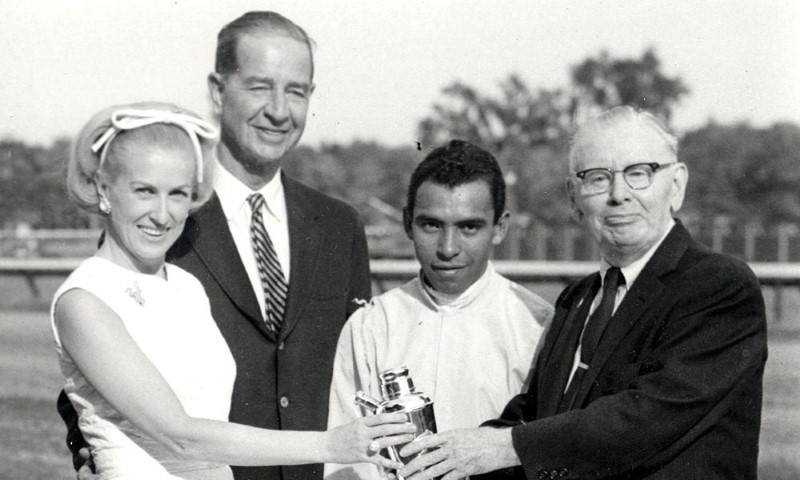

Marylou and Sonny Whitney, jockey Angel Cordero, Jr., and The New Yorker writer Frank Sullivan in the Winner’s Circle at Saratoga in 1967. (National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame)

Of course, Marylou’s story has proven more than just an engrossing tale of historical intrigue from the upper echelons of society—a real-life Great Gatsby, without the unhappy ending. Her story’s also about saving Saratoga and its greatest asset, the racetrack, which hits closest to home for us Saratogians. But where to start? How about Pulitzer Prize-winning sportswriter Walter “Red” Smith’s “directions” to Saratoga: “From New York City you drive north for about 175 miles, turn left on Union Avenue and go back 100 years.” Whitneys and Vanderbilts, scions of racing and society, have been coming to Saratoga since the days of John Morrissey, the bare-knuckle-boxer-turned-Congressman, who first brought Thoroughbred racing here in 1863. The families have been entwined with the fate of Saratoga ever since, and have been part of its trajectory forward after both town and track were threatened time and again with almost certain demise. Railroad baron Cornelius Vanderbilt, Sonny’s namesake, and William Travers were among the track’s founders. Beset by corruption and shut down for the 1896 meet under Gottfried Walbaum, it was Sonny’s grandfather, William C. Whitney, Secretary of the Navy under President Grover Cleveland and a descendant of Eli Whitney of cotton gin fame, who bought the track in 1901 and remodeled it.

Generations of Whitneys and their spouses gradually helped bring the track back, making it into the powerhouse it is today. Sonny’s C.V. Whitney Racing Stable bred or raised more than 450 stakes winners at its Lexington farm alone. Sonny began dispersing his family’s racing stock in his 80s, so Marylou would be free to travel and not have to bother with the business—a historically male-dominated one. After Sonny’s death in ’92, Marylou ended up using a chunk of his estimated $100 million estate to buy back the Whitney broodmares for a stable of her own. She searched for and bought Dear Birdie, a foal by her nickname-sake Hush Dear, for $50,000, just before the mare went up for auction at the Keeneland yearling sale. Marylou’s fledgling Blue Goose Stable—I remember her blue cushions with a blue goose on the five wooden chairs in her clubhouse box near the finish line, at the track—soon evolved into Marylou Whitney Stables. At Marylou’s Opening Day luncheon in 2001, her husband John told me he had high hopes for the new venture. (Ian Wilkes is its trainer today; Nick Zito held the position back then.) “We have 25 two-year-olds in training,” said John. “With Nick’s talent and Marylou’s money, we should have some luck.” As of July 2018, in 1431 starts, Marylou Whitney Stables has 183 wins, 180 places and 191 shows. If you were at Saratoga last summer, you’d have seen the Whitney Stables’ Quick Quick Quick come in second on August 6 and log a win on August 27. The Stables will no doubt have contenders at this year’s Saratoga meet, and, as always, Marylou and John will be there to present the trophy at the $1.2 million Whitney Handicap on August 4, a race named in her family’s honor—and the second richest race at the meet (just behind the Travers).

Marylou and husband John Hendrickson (center) greeting jockey Javier Castellano at Saratoga on August 29, 2010. (Lawrence White)

Now, if a horse has a bird in its name, odds are good it’s a Dear Birdie foal. Marylou, a familiar face in the foaling shed, was there when Birdstone was born. (Birdstone, half sister Bird Town and their mother, Dear Birdie, reportedly recognize Marylou’s voice and look for her in the barn.)

In 2004 Birdstone smashed the hopes of Triple Crown contender, Smarty Jones, at the Belmont Stakes. Marylou seemed more upset than Smarty Jones’ owners, Roy and Patricia Chapman. “I’m sorry we beat you,” she told Mrs. Chapman, who graciously said the better horse had won. Her husband, John, called Birdstone “the little horse who could.” Fresh off his spoiler-maker victory at Belmont, Birdstone came to Saratoga and won the Travers, crossing the finish line as the dark sky opened with apocalyptic thunder, lightning and pelting rain. Standing in the Winner’s Circle with other reporters and photographers, I saw Marylou beaming, but soaked—electric and energized. The successful bird-named bloodline would continue its winning ways, with Birdstone’s daughter, Stone Legacy, coming in second in The Kentucky Oaks in 2009. That same year, Birdstone’s colts Mine That Bird and Summer Bird won the Derby and Belmont, respectively.

In 2010, Marylou was honored with The Eclipse Award of Merit “for a lifetime of outstanding achievement in Thoroughbred racing.” I talked with Stella F. Thayer, President-Treasurer of the Tampa Bay Downs racecourse, who first came to Saratoga in the 1970s with her husband. (She’s also served as the President of Saratoga’s racing museum.) At that point, Saratoga Race Course had reached a nadir, and a proposal had been made to shutter it. “They wanted to close the racetrack at the time,” says Thayer. “Thank God they didn’t do it. Now it’s the most popular [racing] venue [in the country].” Speaking of the Whitneys, Thayer tells me: “Marylou does things with enthusiasm, grace and dazzle,” having supported countless charities and the racing museum, first with Sonny, and then with John. (Marylou’s husband is the current President of the racing museum, by the way.) “They’ve done so much for Saratoga, both past and present, through thick and thin.”

Certainly, Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s construction of the Northway, which reached Saratoga in 1963, and the Saratoga Performing Arts Center (SPAC), which he supported, in 1966, were keys to the city’s resurgence. Also, the latter wouldn’t have been possible without Marylou and Sonny’s generosity; they were among the founders of SPAC and helped finance the racing museum and the National Museum of Dance, which has a Hall of Fame that bears their names. But the city and the track’s turnaround were still a long time coming in the 1970s. One positive result of the city’s neglect? The historic racetrack wasn’t torn down or redeveloped, but rather, stayed the way it was, frozen in time. Oversized wooden Victorian structures—old-fashioned firetraps with spires, uneven floors, constricted Clubhouse boxes with creaky chairs—certainly would’ve been replaced if the money were there. Surprisingly, it wouldn’t be until the 1980s that Saratoga Race Course finally started beating out its Downstate cousins, Belmont Park and Aqueduct Racetrack, on an annual basis. Saratoga attendance rates soared in 1983, and the lead soon widened. “Saratoga was bucking the trend when it took off in the 1980s and 1990s,” Gary McKeon, NYRA President from 1982 to 1994, has said. “No one else was growing, [and] Saratoga took off like a rocket.” As the Saratoga meet was extended from 24 days in 1962, to 30 in 1991, to 34 in 1994, to 36 in 1997, to 40 in 2010, where it has stayed, the upward trend continued.

Marylou Whitney, holding court as usual. (Maria McBride Bucciferro)

By 2017, Saratoga had a total paid attendance of 1,117,838 for the meet. Saratoga’s handle for all-source wagering hit a record-breaking $676,709,490. Marylou didn’t earn her honorary title, “Savior of Saratoga,” for standing by idle. That said, she and Sonny, (and later John) had a lot of help along the way: Their good friends, the late Ed Lewi, famed public relations executive, and his wife, Maureen, come to mind. In the late ’70s, LA County’s Santa Anita Park and NYRA were the only racetrack associations to have marketing departments. NYRA reached out to Ed Lewi Associates for help. “Both the track and the city were very depressed when we first came here in the ’70s,” says Maureen Lewi, Co-owner of the firm, which also did PR for SPAC, the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid and Coca Cola, among others. “Marylou was game for all of Ed’s ideas to promote Saratoga. Saratoga became so ingrained in our hearts. It became our (Sonny, Marylou, Ed and my) mission in life to catapult Saratoga to fame, and Marylou was the star. The media found her fascinating.”

Ed came up with the phrase “the August place to be”—which Marylou tweaked to “the summer place to be,” when racing was extended into July. The Lewis’ plan was simple: “to depict Saratoga as an experience; show that it was more than a wonderful, historic racetrack; it was a place for fun; a place to be seen,” Maureen says. “NBC Nightly Newscame to spend two days shooting a racetrack story and stayed for almost a week after they met Marylou,” she tells me. Vanity Fair, New York magazine and other national publications caught on and did stories, as did East Coast newspapers, and broadcast and cable TV networks. “Nothing was too much for Marylou to do for her beloved Saratoga. She invited celebrities to Cady Hill, hosted a grand ball, dazzled the crowds at myriad events and fundraisers and mingled with all the fans at the track. She rode in carriages, in a hot air balloon, on the back of an elephant and in Greta Garbo’s Duesenberg—all to put the spotlight on Saratoga,” Maureen says. “She certainly earned her title ‘Queen of Saratoga.’”

When Marylou was inducted into the Walk Of Fame at the track in August 2015, everyone from Hall of Fame jockeys Angel Cordero, Jr. and Jerry Bailey to longtime track announcer Tom Durkin and her former horse trainer Nick Zito, paid tribute to her. “You hear so much about people, and some of it is built up,” Zito said at the event. “This is the real deal. There’s no hype. There’s no build-up. Marylou Whitney is a pillar of the sport of racing, a pillar of our community in Saratoga and one of the great ladies that I’ve met in my entire life.” NYRA CEO and President Chris Kay says: “Her generosity is unparalleled. I’ve spoken to many people in Saratoga Springs. They all tell me the same thing. Marylou Whitney saved this town since the moment she arrived nearly seven decades ago.” That she did. And how.